Locked within Rome’s labyrinthine maze of narrow streets stands one of the most renowned buildings in the history of architecture. Built at the height of the Roman Empire’s power and wealth, the Roman Pantheon has been both lauded and studied for both the immensity of its dome and its celestial geometry for over two millennia. During this time it has been the subject of countless imitations and references as the enduring architectural legacy of one of the world’s most influential epochs.

The Pantheon, which now stands on the Piazza della Rotonda, is in fact the third such structure to occupy the site. The original Pantheon was commissioned by Marcus Agrippa, the son-in-law of Emperor Caesar Augustus, and was dedicated in 27BCE. After a fire destroyed much of Agrippa’s original construction in 80AD, Emperor Domitian carried out a reconstruction effort (the exact extent of which remains unknown). However, when a lightning strike burned the Pantheon down yet again in 110, the structure which Emperor Hadrian put in its place was of an entirely new design.[1]

The reign of Hadrian arguably represented the greatest 'Golden Age' of the Roman Empire. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the landlocked Caspian Sea in the east, the Empire’s territory encompassed southern and western Europe, northern Africa, and a sizable swath of western Asia – the furthest that its borders would ever reach. It was also the most economically prosperous period in Roman history, with unprecedented regional stability allowing trade to pass freely through the various provinces. The many cities of the Empire underwent expansive building programs, bringing public baths, forums, theaters, and circuses to citizens on three continents. In such an era of peace and prosperity, when all of Rome seemed to be under harmonious control, it was only fitting that a monument be built in the capital to represent this ideal state of affairs.[2]

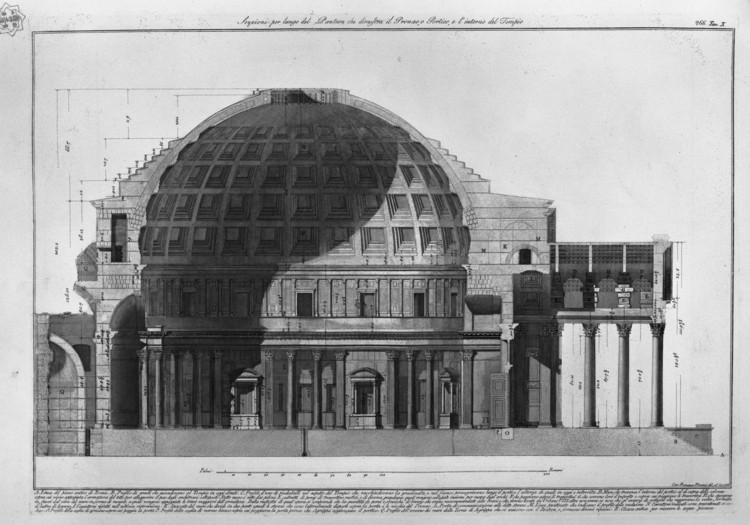

Formally, the Pantheon is striking in its simplicity. It is—put simply—a large drum capped by a dome, with its north-facing entrance marked by a portico. Inside the drum is a single cavernous space, with natural light from a 9 meter-wide (30 foot) oculus spilling down onto alternating triangular and rounded altars that mark the perimeter of the room. The floor and walls of the interior are surfaced with fine stone sourced from across the Roman Empire, including granite and various colored marbles; the coffered ceiling is exposed concrete.[3] This dome was the largest in the world by a significant margin, a superlative it would retain until the construction of Brunelleschi's engineering marvel at Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence in 1436, thirteen centuries later.[4]

Enabling this seemingly simplistic geometry was an elaborate structural system, the culmination of decades of progress in Roman engineering technology. The 6 meter (20 foot) thick walls of the rotunda, while appearing monolithic from the outside, conceal a carefully-planned network of voids and arches that act as eight piers supporting the weight of the dome above. The dome itself was made possible by the Roman material innovation of concrete. Concrete vaults were used to great effect in a number of structures during the reign of Hadrian’s predecessor (and adoptive father) Trajan, laying the theoretical framework for the construction of the Pantheon’s dome. Here, unlike in the walls, the structural solution is plainly visible: the five rows of coffers, while aesthetically appealing, reduce the deadweight of the dome between its structural members, limiting the stress placed on the arches hidden within the walls of the rotunda.[5,6]

The carefully premeditated planning of the rotunda stands in ironic contrast to the relatively disjointed portico. Rather than joining directly to the rotunda, the pediment connects to a rectangular transitional block, which features the outline of a pediment at a higher elevation than that which crowns the portico. This apparent misalignment led several architects to hypothesize over the centuries that the portico and rotunda were built at separate times by separate emperors, with one having been an awkwardly-proportioned addition to the other. Examination of the foundations and stamps on the bricks used in the structure, however, indicate the entire Pantheon was built as one cohesive project.[7]

The mismatch of the portico and rotunda is evidently the result of logistical issues in acquiring stone at the size specified by the Pantheon’s builders. A pediment at the height implied by the outline on the transitional block would require taller, thicker columns than those used in the temple as it is built; however, unlike those smaller columns, the hypothetical original design would conform neatly to the established proportions used in religious Roman architecture. The cornice line of the roof would also connect to the middle cornice line encircling the rotunda, whereas the existing roof does not seem to relate to any part of the structure. Despite the sheer financial power of Hadrian’s empire, however, adequate material could not be quarried for both the Pantheon and the simultaneously-constructed Trajan’s Temple, and the former was subjected to an ungainly compromise in order to expedite construction of the latter.[8]

The awkward proportions of the portico could not diminish the impact—or the meaning—of the vast space enclosed within the rotunda. The diameter of the rotunda’s interior is almost exactly the same as its height: 43.4 meters (142.4 feet). Combined with the hemispherical volume expressed within the dome, the space implies a perfect sphere.[9]

The cosmic implications of this geometry are clear: the sphere was an analogy for the heavens, all contained within the Pantheon’s concrete walls. At the highest point of the heavens (in this case, the oculus) shone the light of the sun, casting its beams on the various statues of planetary deities that occupied the niches in the walls as the day wore on. While the gods and heavens were honored in this symbolic design, however, it was the Roman Empire itself which was truly glorified. The cosmos embodied and enclosed by the Pantheon represented the Empire, its disparate lands and peoples held together by the celestial authority and perfection of Rome. Its name may imply religious consecration, but the Pantheon was truly a testament to the might and glory of a worldly government.[10]

As a symbol of the Empire, the Pantheon was subjected to a series of indignities as Rome began its slow decline over the following centuries. In the early 7th Century, the Emperor Constantius II of the Eastern Roman Empire visited Rome and officially gave the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV for use as a church; before doing so, however, he took the gilded bronze tiles which once covered the roof of the dome for his own use. Now known as the Church of St. Mary of the Martyrs, the Pantheon had its golden roof replaced by one of lead. Two centuries later, Pope Urban VIII ordered the removal of several large bronze beams from the portico for use in Bernini’s altar canopy at Saint Peter’s Basilica, as well as for cannons at the Castel Sant’Angelo (the fortified Roman residence of the Pope). As a consolation gesture, Urban commissioned a pair of bell towers to be added above the portico; these towers were generally considered ugly and out of place, however, and were removed in the 19th Century.[11]

Perhaps thanks to its repurposing as a church the Pantheon is one of the best-preserved monuments of Ancient Rome. Its celebrated dome remains the largest in the world to be built from unreinforced concrete and, in spite of the addition of Christian altars and frescoes, its design remains largely the same as it did under Hadrian’s rule. Its form has served as the inspiration for an entire canon of buildings since the Renaissance, among them the Panthéon in Paris, the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, the library at the University of Virginia, and the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.[12, 13, 14] Between its architectural legacy and its own endurance, the Pantheon stands as a lasting testament to the faded glories of the Roman Empire – a monument as eternal as the city in which it stands.

References

[1] Marder, Tod A., and Mark Wilson Jones. The Pantheon: from Antiquity to the Present. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015. E-book.

[2] Kostof, Spiro. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. p217-219.

[3] Platner, Samuel Ball, and Thomas Ashby. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1929. p382-386.

[4] "Pantheon Rome." Pantheon Paris. Accessed December 20, 2016. [access].

[5] Lancaster, Lynne C. Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. p97-98.

[6] Cowan, Henry J., and Trevor Howells. A Guide to the World's Greatest Buildings: Masterpieces of Architecture & Engineering. San Francisco, 2000: Fog City Press. p24.

[7] Jones, Mark Wilson. Principles of Roman Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000. p200-202.

[8] Jones, p204-210.

[9] Stamper, John W. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005. p196.

[10] Kostof, p218.

[11] Papandrea, James Leonard. Rome: A Pilgrim's Guide to the Eternal City. Eugene: Cascade Books, 2012. p34-35.

[12] “Pantheon Rome.”

[13] King, Ross. Brunelleschi's Dome. London: Chatto & Windu, 2000.

[14] Fiederer, Luke. "AD Classics: University of Virginia / Thomas Jefferson." ArchDaily. December 08, 2016. [access].